Reflections on the flooded forest

Anne Magurran

December 17, 2020

One of my most vivid memories is of waking up, to a dawn chorus of howler monkeys, in a floating house laboratory in the Amazonian flooded forest.

At night I could hear the river dolphins hunting fish in the water below us, while in the mornings I watched the caiman and pirarucu as I drank tea on the deck of the floating house.

I have been to Mamirauá Reserve in the Brazilian Amazon a number of times now, working with Helder Queiroz and Peter Henderson on its fish diversity, but that initial sense of being somewhere special has stayed with me.

Mamirauá Reserve, and the Institute that runs it, is a great example of conservation in action as it supports the sustainable development of the people who live there while documenting and protecting the organisms on which they depend. It demonstrates that solutions that support both people and nature are possible.

The wildlife in the area was first formally documented by Victorian Naturalist Henry Walter Bates in the 1850s. Bates drew on his observations of Amazonian wildlife when formulating his thoughts about ecological and evolutionary processes, including what we now call “Batesian Mimicryâ€. Down the years Mamirauá has attracted many biologists. Bill Hamilton was a regular visitor and was there during my very first visit. We remember Bill for his contributions to evolutionary theory, but he was also a fabulous naturalist, and could name every plant, and many animals, in the flooded forest. I have fond memories of listening to him recount tales of his experiences in the field. One was of being bitten a botfly, which he regarded as having such a fascinating life cycle that it was a privilege to have been parasitised by it.

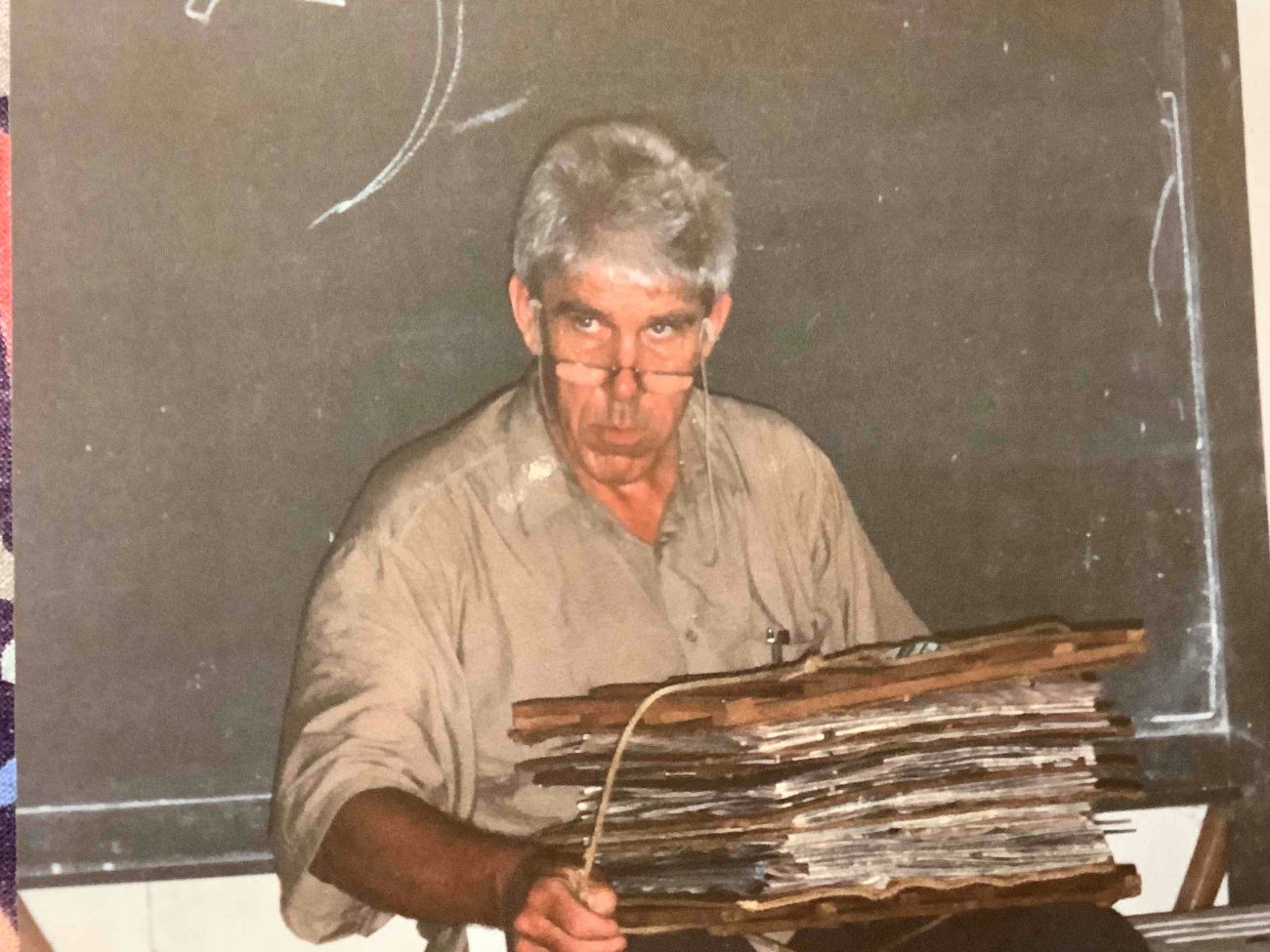

Mamirauá brought home to me the considerable challenges in making robust estimates of biodiversity, and quantifying its change over time. The flooded forest covers a large area, much of it relatively inaccessible, and the need to live, and work, on the water adds to the logistical complexities of doing science there. And, of course, the biota is stupendously diverse. Sampling is hard work, and species identifications can be difficult. The few lines about sampling methods in a paper do not begin to convey the sheer effort involved in data collection, none of which would be possible without the contributions of local scientists and field assistants.

Sitting on the deck of the floating house, watching the reflections of the trees in the water, reminded me why I am an ecologist, and how lucky I am to have been able to work in such a remarkable place. But being there also made me realise how important it is to have good data, how hard it can be to collect those data, how essential it is to recognise the efforts and people involved, and how vital it is to ensure that this irreplaceable information is preserved.

This story is published under a CC-BY NC licence. Photographs are by Anne Magurran unless specified otherwise.