Trial by… fog

Cher Chow

October 21, 2020

In February 2019 I was part of a team conducting reef fish biodiversity surveys in Hong Kong. This was essentially a two-year field season filled with long days, often spent sopping wet in isolated areas. Conditions I’m sure are relatable to many biologists. While most of our survey sites were easily accessible from the city’s piers, some required a 40-minute speedboat ride along the rocky coastline of a towering UNESCO Geopark. Despite the longer commute and tricky navigation, these were some of my favourite sites to dive at because the steep cliffs usually meant finding more interesting critters and fish.

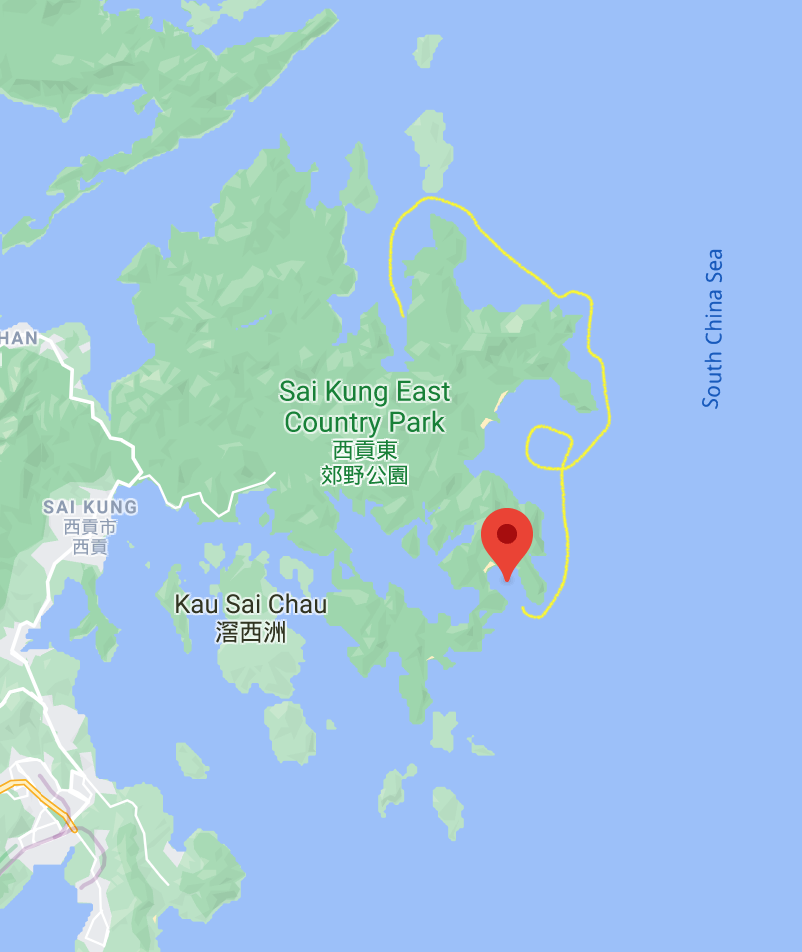

Our survey days had two dives: one at noon, and another 1 hour after sunset. On the night dive that we were wrapping up our dry season, we had to tackle one of those tricky survey sites, called Long Ke. Our skipper, Ze Fu (å§å¤«), was one of what we call “water people” in Cantonese— a multi-generational skipper and fisher. He expertly navigated around the craggily shallows of the coastline, even in the dark.

The actual dive went well: I found a huge cuttlefish and some rare red skeleton shrimp. But the adventure started after we surfaced. During our 80-minute dive, the thickest fog I’d ever seen in Hong Kong came rolling in. It was ominous, like a scene straight from Pirates of the Caribbean. Even Ze Fu, with all his seafaring expertise, had rarely seen fog like this.

The way back to the dive centre was perilous even without the fog, but now visibility was limited to two meters in front of the boat. We strapped our dive torches to our wrists, pointed them outwards, and slowly navigated back. The light beams on the speedboat scattered in the fog and it was all a greyish blur.

Ze Fu had me looking at his GPS system to direct his steering, while he kept his eye on his compass. We knew there was a point coming up around Conic Island with lots of little mounts near the surface. Ze Fu was going extra slowly around this point, following the GPS. Then, suddenly, as the waves crashed against the mounts our dive buddy saw them exposed dangerously close port-side. We were only a metre away from crashing into them and narrowly missed it. The GPS had lagged, and Ze Fu didn’t see it coming. We slowed to ~1 knot and meandered our way across the bays.

Somewhere along the first rocky bay past Long Ke, I realised Ze Fu was going in a circle, despite my instructions to tell him to go northeast. My dive buddies were looking on port and starboard to keep a lookout with their torches in case more mounts would come up again, and they noticed that Ze Fu was going opposite of my directions. He was reading his marine compass wrong. One of my co-workers, Jeffery, realised this and started translating my directions into “left” or “right” instead. But Ze Fu was mixing those up too! Jeffery and I solved this by placing ourselves at port and starboard and used us as directions to make sure Ze Fu didn’t get confused anymore. The slow and improvised navigation teamwork continued for who knows how long.

Exhausted, cold, and hungry, we finally made it to the dive centre. It was more than an hour since we surfaced, and I have never been more sure of my navigational skills since then…